I forgive you. For growing a capacity to love that is great, but matched only, perhaps, by your loneliness.

Of all the comforting words directed my way as a young widow, the well-meaning “you had true love, some don’t experience that at all” never helped me. What I heard, I’m sure not intended, was that I was selfish to want deep love again, that what Brian and I had was profound, and experiencing that kind of love even once is plenty for a lifetime. Yes, we had a great love, we were soul mates. What we experienced together wasn’t just a trusting love that sustained us through better and worse, sickness and health, but a shared and exponential ability to feel new depths and versions of love. A love that evolved through the mundanity and intensity of our life with kids, pets, and across three different states. Why wouldn’t I want that again?

The capacity to love didn’t die along with Brian nor is it reserved just for him. I have a big heart that, from time to time when I am consumed by grief, snugly holds Brian’s memory as it swells to every edge. The sadness I feel is the experience of love that no longer has a place to go. Then miraculously my heart keeps its shape when the grief subsides. His memory settles in a comfortable corner (not too far away) and my heart fills with the lightness of love. Sometimes romantic love, more often an agapic love activated by me, my friends, nature, family, humanity, and a warm, universal energy that connects us all. This kind of love lifts and carries me through. Until the pangs of loneliness show up and seek center stage, momentarily obscuring all else, reminiscent of grief, but characterized by a desire for love that also has no place to go.

“Phase One,” beautifully written by Dilruba Ahmed, and the third poem in Poetry Unbound, offers a litany of faults and a generous refrain of forgiveness. Reading it reminded me of how hard I am on my heart. I urge it to lighten up and not expect too much, blame it for falling too fast, grieving too long, and feeling too much. The title of this post is a stanza in the poem, toward the end, as the list of faults grows and the real culprits are finally named: love and loneliness. When I first read it, I focused on the loneliness, attention-hog that it is, glossing over the embedded compliment. I read it once more and reflect on the positive quality of capacity. And I realize that my capacity to feel the strength, nuance, range, distinctness, and intertangling of emotions, all rooted and related to love, is enormous. I can feel the mass of these emotions, the weight of grief, the gravitational pull of loneliness, and the lightness of love. What a gift. I don’t forgive my capacity—on the contrary—I embrace it, love it, and hope it continues to grow as long as I’m alive.

Let me be ok.

How often did I utter this simple plea after I moved back home to New Mexico? Please, let me be okay. It would start desperate, while sobbing, feeling incredibly alone, and not at all sure that I could do the big things, like move across the country with a U-haul full of stuff to a home I hadn’t seen before, to a place I hadn’t lived, without a job and not much of a plan. It felt too hard, too much, too scary, and to top it off I brought an innocent bystander, my youngest child (and her cat) with me, who does that? (People. people do.)

Then my request would be softer, while meditating, after the cathartic sob, looking at my surroundings, thinking of the luck I’ve had, and feeling an ounce of optimism creep in. But the tiny verb in my prayer was worth consideration. Let. Finding this one permission-seeking word in Kei Miller’s* inquiring poem Book of Genesis (itself being the preeminent story of Let) spurred on all this thought of my wordplay creating reality, eventually shifting my perspective from a prayerful “let me be okay” to a calmer “I am okay” despite whatever drug me down. At times I would recall the more practical phrase 'suck it up, buttercup' that Brian was quite fond of. He often directed it at our kids (poor souls), but it helped further shift my perspective. I could hear his sharp advice and knew to be okay, one had to accept the current situation and actually BE.

But was it him I was asking to begin with? Who do we turn to when we are at our lowest? When we are feeling doubt, uncertainty, or fear. I’ve never had a direct communion with God, rather I feel a connection to a spiritual Universe—to the collective energy of all living things** and all who have died, the stars above us, the ground below, all of it of us. But when I need more than stardust, I can recognize a singular consciousness—in the form of a nameless, loving energy, or yes, Brian’s personality and voice, or even, occasionally, my dad, now 26 years gone. At these times of utter aloneness, what mattered wasn’t who as much as what. I need to be reassured by a spiritual other moving me from “let me” to “I am,” someone to confidently say, “You are okay.”

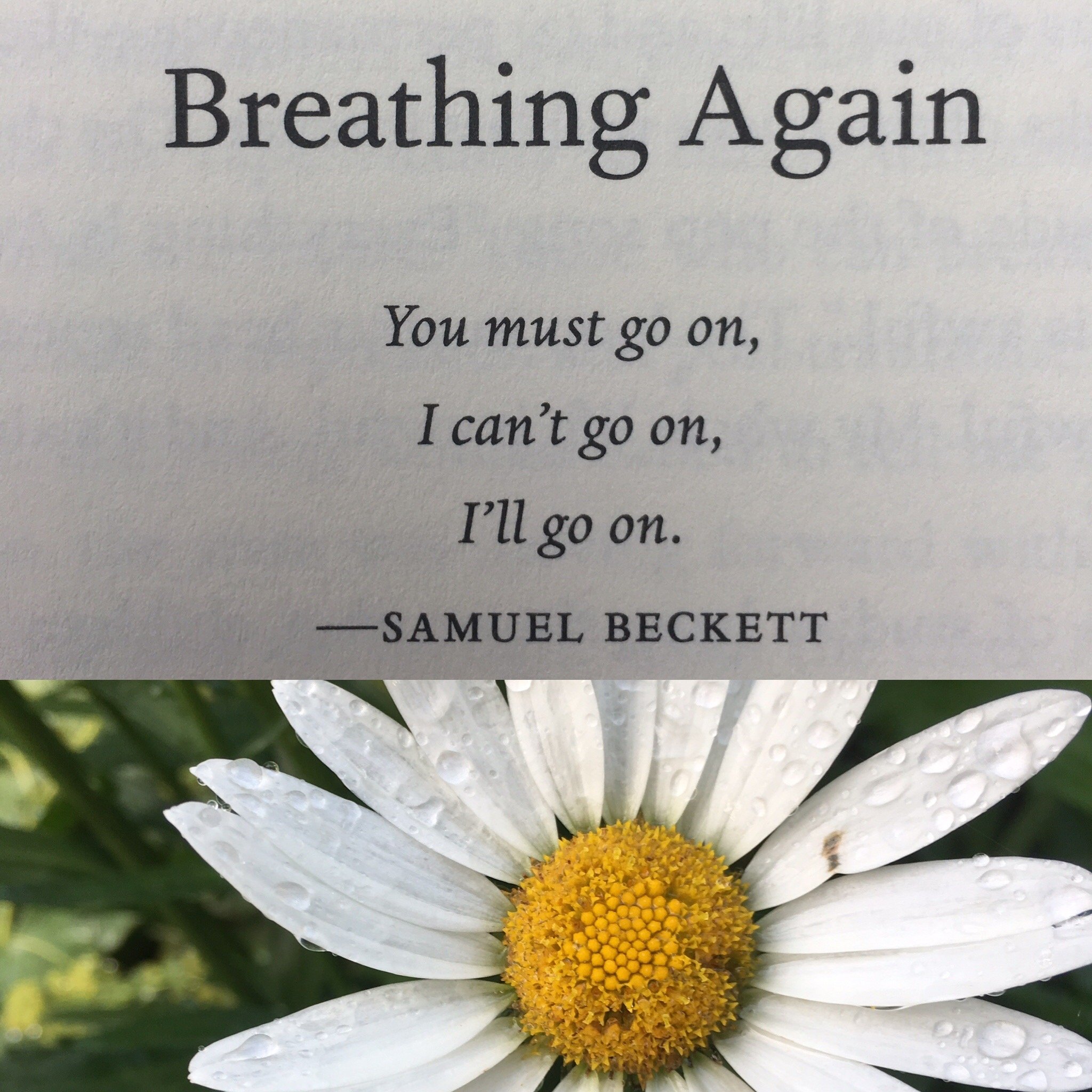

So I would hear those words, from someone come and gone, a Higher Power, or my highest self. You are ok. Really. You are. Like the singular flowers that go it alone, so many of them I’d see on my walks, coming through sidewalks, or in a patch of grass. With a little more strength, I could move to the next day, the next moment, the next experience—which I would simply let. be.

——

*This was the second poem in Poetry Unbound. Simple and profound. Kei Miller is a Jamaican poet who teaches Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow and often explores themes of identity, language, and place. Were all these poets hand-selected for me? I think so.

**I am not alone, roughly 3 in 4 people believe in a higher power, be it a God, gods, or some other divine source or universal energy. You can learn more in this 2023 Fetzer Institute-funded spirituality research study and report I co-authored, with a particular focus on how beliefs and practices changed during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

A woman. By a river. Indestructible.

My truest story.

I haven’t been by the river in well over a year, the Chama River, where my late husband's ashes flow and where we spent so much time as a young couple. But I think of it often. I like to think Brian’s ashes are still there, flowing and clinging, though it has been over seven years since the kids and I threw most of his ashes into this wild river. The water itself isn’t much to look at, muddy from erosion, it is surpassed in beauty by the curves of its container and the multi-colored cliffs and mountains that rise and hold the land in northern New Mexico, just a mile west of Ghost Ranch, aka Georgia O-Keefe territory. Yet, it is remarkable water.

The last time I went to the Chama, on what would have been Brian’s 58th birthday, I lay as close as possible to the edge, finding a flat outcropping of rocks to stretch out on my back. I closed my eyes to focus on the sound of the water, made louder by its volume and urgency. Opening my eyes, I rolled over and watched the water closest to me, where it pooled up, resting in little protective spaces along the edge, then into the current once again. It reminded me of new skaters on the edge of a roller rink, holding on to the edge for dear life (Life), then, taking a deep breath, letting go, stumbling a bit but moving on, just like the water catches a stick or two, some stacked rocks, a little mud, then flows on to join the current.

As I read the first poem in Poetry Unbound*—Wonder Woman by Ada Limón—I parse this line: A woman. By a river. Indestructible. While the author** describes surviving life with chronic pain, I think of resilience borne of grief and fast-moving currents that take us without consent. Sometimes we let go willingly, not knowing how we will get through but trusting we will. I think of me, in my memory, so many times, by a river. I think of figurative currents in my life that carried me back to New Mexico. So I could witness the real rivers that keep moving, the mountains that give perspective, and the sky that is always huge, always hopeful. And heal.

I’ve come to know that healing never ends, it ebbs and flows, shape-shifts, changing what we need and what we see along the way. Often, we are unaware of the forces that propel us forward, just that we’ve somehow moved through. At other times, we know exactly what we need or what is helping us along. Coming home to New Mexico would do wonders for my hurting soul, I knew that. And lying by the river in meditation would remind me of my resilience. A woman. By a river. Indestructible. My transforming in place has taken many turns and is often opaque, just like my beloved Rio Chama, but it keeps happening as I keep going, resting when needed and forever connected to the river’s flow.

—

*I have one or two copies of Poetry Unbound I’d love to gift. I was so taken by it and how it helped me, that I rushed and bought a dozen copies, doling them out like Bibles whenever someone expressed a slight interest. Send me a comment and let me know if you would like a copy.

**Ada Limón is the current U.S. Poet Laureate, the first Latina to hold the position, and the first to be renewed for a second term. I also discovered that her goal is “to use poetry to draw attention to the natural world, and to promote the idea that poetry can help people connect with their emotions and heal.” 🤍